Miscarriage care delays have been linked to the tragic deaths of two mothers who were left waiting for urgent medical help. Both women, Brenda Yolani Arzu Ramirez and Porsha Ngumezi, spent hours in hospitals without receiving the emergency treatment they needed. Their conditions worsened until it was too late, leaving families devastated and medical experts alarmed.

The cases have sparked outrage and debate about the state of women’s healthcare and the role that restrictive laws may have played. Both mothers required procedures to remove pregnancy tissue, but were forced to wait while their health rapidly deteriorated.

Doctors had already warned that abortion bans in Texas could place women experiencing miscarriage at risk of death. For Brenda and Porsha, those warnings became reality. Experts say their deaths were a direct result of hospitals withholding the abortion-related care that was medically necessary.

The stories of these two women triggered emotional discussions online, with many calling the situation evidence of how dangerous restrictive laws can be for women’s health. Comments poured in on platforms like Reddit, where one user wrote that women were being treated as “livestock,” while another called it “a war against women.”

Brenda’s Miscarriage Story

Brenda Yolani Arzu Ramirez was 22 weeks pregnant when her baby died in the womb. At that moment, she faced severe risks, including a deadly infection. She was admitted to a hospital in Austin, but instead of urgent treatment, she waited for hours as her condition spiraled into sepsis.

She had arrived in November 2021, prepared to deliver her stillborn child. Her OB-GYN suspected she required immediate intervention, yet no emergency care was provided when she first came in.

Brenda’s medical history already placed her in a high-risk category. She had experienced preeclampsia in past pregnancies, a condition that can cause dangerously high blood pressure. Both of her previous children were delivered via cesarean section. This pregnancy, however, presented far greater risks than her earlier ones.

As her condition worsened, Brenda developed fever, vomiting, breathing difficulties, and intense headaches. Despite the warning signs and her history, she remained untreated for far too long. At only 22 and a half weeks pregnant, a cesarean was not considered viable. What she needed was immediate intervention, but she did not receive it.

Hospital staff recorded that Brenda had a fever of 103°F and a dangerously low white blood cell count. An ultrasound confirmed that her baby had died. By then, the legal climate after the overturn of Roe v. Wade had left doctors fearful of lawsuits for performing abortions, even when medically necessary.

Her OB-GYN recommended a dilation and evacuation procedure, but the transfer to St. David’s North Austin Medical Center never happened. Instead, she was given Pitocin to induce labor. Hours later, she delivered vaginally, but by then her infection had already progressed into full sepsis.

Her body began to shut down. She suffered organ failure, and two weeks later, after a seizure and cardiac arrest, Brenda died.

Medical experts reviewing her case said she should have received a D&E immediately. Dr. Deborah Bartz of Harvard Medical School called her death a tragic example of how delays in miscarriage care can cost lives.

Porsha’s story

The second case was equally devastating. Porsha Ngumezi, 35, miscarried during her first trimester. She endured hours of waiting in the emergency room, passing large clots while her health deteriorated.

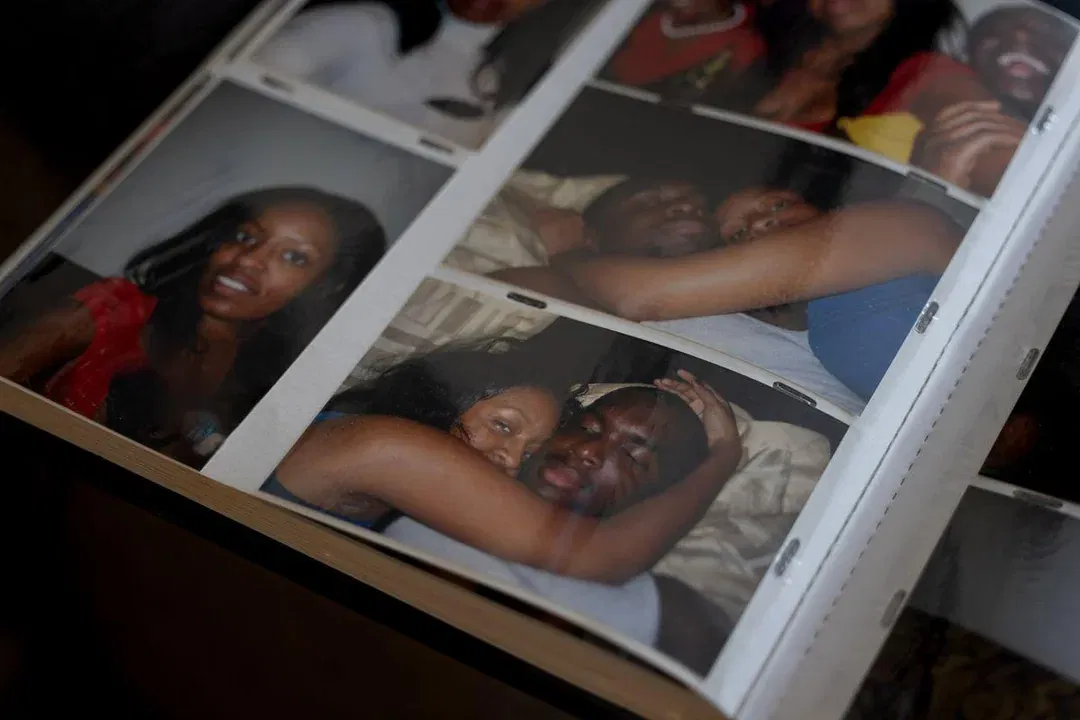

She and her husband had been eager to welcome another child. But when she began spotting early in the pregnancy, doctors advised her to carefully monitor the symptoms.

Porsha’s health conditions made her more vulnerable. She suffered from anemia, a blood disorder that reduced her platelets, and carried the sickle cell trait. By June 2023, at 11 weeks pregnant, her bleeding worsened, and she sought help at Houston Methodist Sugar Land Hospital.

Two hours later, she miscarried in the hospital restroom. She passed grapefruit-sized clots and believed she had expelled the fetus, but the toilet flushed automatically before she could confirm. Distressed, she texted her husband: “I just had a miscarriage in their restroom. I haven’t stopped bleeding.”

Her husband was alarmed and asked if doctors were addressing her bleeding. She explained that she had to stay so the staff could monitor her. By the time he arrived, Porsha had been at the hospital for four hours. Her blood pressure had dropped, and her condition was clearly deteriorating.

Doctors gave her fluids and blood transfusions, but the bleeding did not stop. A staff member even questioned whether it was safe to move her to a less urgent unit.

Two possible treatments were discussed: misoprostol or a dilation and curettage (D&C). Misoprostol was chosen, despite her mother’s pleas for the surgical option.

As more time passed, Porsha’s chest began to hurt, and she had trouble breathing. She eventually went into cardiac arrest. Doctors tried to revive her, but she was pronounced dead shortly after.

Dr. Bartz later explained that Porsha’s death was the result of repeated delays and the failure to act with urgency. She noted that doctors had not listened carefully to Porsha’s symptoms or her family’s concerns.

Medical experts reviewing both cases agreed that the lack of immediate care was fatal. In Brenda’s case, Dr. Bartz stated that a D&E procedure should have been performed right away, especially when she arrived at the second hospital.

For Porsha, Dr. Rebecca Cohen explained that her blood conditions made her bleeding especially dangerous. The presence of large clots was a clear sign that a D&C was urgently needed. Cohen believed that if Porsha had been treated at her own hospital, she would likely still be alive.

Other experts emphasized how critical timing is in these situations. Once sepsis begins, every minute counts. Dr. Nancy Binford noted that even small delays can determine whether a patient survives.

Dr. Karen Swenson raised another concern. She said that restrictive laws had created fear among doctors. According to her, physicians may hesitate to act because they worry about legal consequences, even when patients’ lives are at risk.

When contacted, St. David’s HealthCare, which oversaw the hospitals where Brenda was treated, said it could not comment directly on her case because of privacy laws. However, the organization highlighted that its North Austin facility is a Level IV Maternal Facility equipped to handle complex pregnancy and postpartum care, including both induction and D&C procedures.

In its statement, the hospital said that each pregnancy case is unique and complex. It added that access to procedures like D&E or induction may be limited in certain settings, especially at later stages of pregnancy, which can complicate decisions.

Houston Methodist, where Porsha was treated, responded that it follows Texas law, including abortion restrictions. It emphasized its status as a faith-based system with a long-standing policy to perform termination only when necessary for the safety of the patient.

Following Porsha’s death, her husband filed a malpractice lawsuit against the hospital, two doctors, and physician groups. That case is ongoing.

The stories of Brenda and Porsha highlight the tragic consequences of miscarriage care delays. Both women needed urgent procedures, but instead, they waited until it was too late. Their deaths have become symbols of the risks that restrictive laws and fearful medical practices can pose to women’s health.

Medical experts agree that both cases were preventable. They stress the importance of timely miscarriage care and the need for doctors to act without hesitation. For families like Brenda’s and Porsha’s, the loss is irreversible. For the wider public, their stories serve as painful reminders of the human cost when medical decisions are delayed.